Ansel Adams: Visionary

March 15, 2016

Ansel Adams was an only child, born to old parents in San Francisco on February 20, 1902. He was the only child of businessman Charles Hitchcock Adams and Olive Bray, and the grandson of a timber baron. Adams’ family home was in located in the coastal Golden Gate area of San Francisco. It was there that Adams developed an early appreciation for nature.

Ansel Adams was an only child, born to old parents in San Francisco on February 20, 1902. He was the only child of businessman Charles Hitchcock Adams and Olive Bray, and the grandson of a timber baron. Adams’ family home was in located in the coastal Golden Gate area of San Francisco. It was there that Adams developed an early appreciation for nature.

He was a shy child, possibly dyslexic, and subsequently he did not do well in school. He was ultimately home schooled, which led to solitary time spent walking along the still undeveloped and wild coastline. At twelve years old Ansel Adams learned piano on his own, and went on to pursue piano as his career. However, in 1916 Adams first visited Yosemite, which changed his passion from piano to photography. It was there in Yosemite that he would take up the camera, a Kodak No. 1 Box Brownie, which was a gift from his parents. Ansel Adams would ultimately spend quite a bit of time yearly at Yosemite, until he passed away on April 22, 1984.

Adams joined the Sierra Club in 1919 and subsequently spent the next “four summers in Yosemite Valley, as “keeper” of the club’s LeConte Memorial Lodge.”[1] This would prove to be quite opportune for Adams, as he became friends with many of the leaders of the Sierra Club and became involved with the early conservation movement. It was here at Yosemite that Adams would also meet his wife, Virginia Best. Adams involvement with the Sierra Club was pivotal to his early career as a photographer, with publication of his both his writings and photographs in their 1922 Bulletin and then a “his first one man exhibition in 1928 at the club’s San Francisco headquarters.”[2] Adams began to see the potential to make a modest living as a photographer through his continued involvement with the Sierra Club.

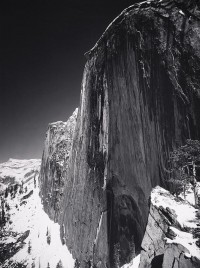

In 1927, Ansel Adams took his famous photograph, “Monolith, the Face of Half Dome.” It was to be his first “fully visualized photograph.”[3] Adams states that to achieve what he visualized with the camera he would need to use a “deep red filter,” which would reduce “the light by a factor of 16, to allow enough light to hit the negative he had to keep the shutter open for a 5 seconds.”[4] This was the first step in Ansel Adams developing his own unique style and techniques that would lead to the Zone System, a fundamental methodology in photography, formulated by Ansel Adams and Fred Archer. Adams book, The Negative describes the Zone System in detail.[5] During this same time, Adams met a San Francisco arts patron, Albert M. Bender, who upon meeting initiated the first publication of Adams’ early work. Bender’s patronage “changed Adams’ life dramatically.”[6]

Monolith – 1927:

Monolith, as mentioned above, was a creative turning point for Adams. He had two plates with him when he took the photographs. He had blown the first shot using a yellow filter to capture what he described as “the majesty of the sculptural shape of the Dome in the solemn effect of half sunlight and half shadow.”[7] However, he succeeded in “visualizing” what he saw to his second and last unused plate of the day. The technical details of Monolith are as follows[8]:

Monolith, as mentioned above, was a creative turning point for Adams. He had two plates with him when he took the photographs. He had blown the first shot using a yellow filter to capture what he described as “the majesty of the sculptural shape of the Dome in the solemn effect of half sunlight and half shadow.”[7] However, he succeeded in “visualizing” what he saw to his second and last unused plate of the day. The technical details of Monolith are as follows[8]:

- Camera: 6 1/2 by 8 1/2 Korona View camera

- Glass plates: Wratten Panchromatic

- Lens: Tesar formula lens of 8 1/2 focal length

- Filter: red Wratten No. 29 filter

- Exposure: 5 seconds at f/22

As previously noted, Monolith was a significant work in Adams career as a photographer because of the technique used. The composition of light and shadows with strong the vertical lines of the rock formations bring the viewer into the depths of the Half Dome, which is the center of interest in the photo. (Adams, Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park)

In Joshua Tree National Monument – 1942 (Printed 1950)

In Joshua Tree National Monument is an interesting composition of a stone outcropping with a lone Joshua Tree off to the lower left of the photo. The eye is drawn in to the Joshua Tree, the round stone in the lower center and the peaks of the stones in the upper edge (center) of the photo. The light is to the back, left of the photo casting shadows into right side of the composition with a long depth of field. The photograph is part of the Ansel Adams collection at The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Printed in 1950; it is a “gelatin silver print, 7 1/2 in. x 9 1/2 in. (19.05 cm x 24.13 cm).” [9]

In Joshua Tree National Monument is an interesting composition of a stone outcropping with a lone Joshua Tree off to the lower left of the photo. The eye is drawn in to the Joshua Tree, the round stone in the lower center and the peaks of the stones in the upper edge (center) of the photo. The light is to the back, left of the photo casting shadows into right side of the composition with a long depth of field. The photograph is part of the Ansel Adams collection at The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Printed in 1950; it is a “gelatin silver print, 7 1/2 in. x 9 1/2 in. (19.05 cm x 24.13 cm).” [9]

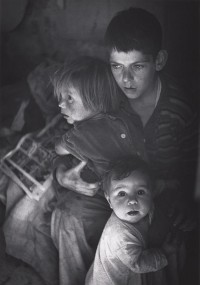

Ansel Adams body of work is so large and diverse. Clearly nature and landscape were the key genre for Adams work, though he also did some portrait and reportage work as well. A striking example of his reportage or documentary work is the photograph, Trailer Camp Children, taken in Richmond, California in 1944.

Trailer Camp Children, Richmond, California – 1944

There are three children pictured in Trailer Camp Children, a young boy with two younger children. The children’s faces each embody despair with vacant looks on each child’s face cast in different directions. There is a soft light cast from the cent left of the photo, causing each face to light up in the glow of their apparent struggle. Although a post Great Depression photograph, the image speaks to the same stark and striking qualities that embodied Dorothea Lange’s photographs of that era and genre. Stepping away from the spectrum of landscape and nature, Ansel Adams revealed his sense of social justice, which was primarily driven by his conservation work. Ansel Adams “partnered with Dorothea Lange for a number of stories”[10] featuring their documentary photography. The medium of the print was a “gelatin silver print.”[11]

There are three children pictured in Trailer Camp Children, a young boy with two younger children. The children’s faces each embody despair with vacant looks on each child’s face cast in different directions. There is a soft light cast from the cent left of the photo, causing each face to light up in the glow of their apparent struggle. Although a post Great Depression photograph, the image speaks to the same stark and striking qualities that embodied Dorothea Lange’s photographs of that era and genre. Stepping away from the spectrum of landscape and nature, Ansel Adams revealed his sense of social justice, which was primarily driven by his conservation work. Ansel Adams “partnered with Dorothea Lange for a number of stories”[10] featuring their documentary photography. The medium of the print was a “gelatin silver print.”[11]

Pioneer Mill, Cimarron, New Mexico – 1961

Pioneer Mill is a photograph taken much later in Adams career. This circa 1961 photograph caught my eye because of Adams use of a framing in the picture. The building is framed within what appears to be a large simple gateway connected to a fence on either side. There is a long depth of field in the photograph, signaling a closed down aperture. The light is on the building and the frame and the background trees pull the eye in from the road alongside the mill building that comes from the lower right area of the photograph. Pioneer Mill is also a gelatin silver print.[12]

Pioneer Mill is a photograph taken much later in Adams career. This circa 1961 photograph caught my eye because of Adams use of a framing in the picture. The building is framed within what appears to be a large simple gateway connected to a fence on either side. There is a long depth of field in the photograph, signaling a closed down aperture. The light is on the building and the frame and the background trees pull the eye in from the road alongside the mill building that comes from the lower right area of the photograph. Pioneer Mill is also a gelatin silver print.[12]

Throughout his life and career, Ansel Adams championed environmental issues, the “preservation of wilderness” and the importance of the national park system. As an environmental activist, Adams “fought for new parks and wilderness areas, for the Wilderness Act, for wild Alaska and his beloved Big Sur coast of central California, for the mighty redwoods, for endangered sea lions and sea otters, and for clean air and water.”[13] His love of nature and the wilderness clearly stood out in his work, and it is his work that helped to save that vast wilderness that he loved so much. In fact, a “vast amount of true and truly protected wilderness in America, much of it saved because of the efforts of Adams and his colleagues.”[14]

Ansel Adams extensive body of work has influenced a great number of modern day photographers including myself. Ansel Adams was an American icon who wholly romanticized the wilderness with photographs that will remain as timeless as Thoreau’s Walden and Emerson’s Nature. His work typically appears to have been shot with the aperture stopped down as far as possible to achieve a long depth of field. In viewing his work, one sees that Adams was a master for manipulating the scene before him, choosing carefully the angle at which he shot, the line of the horizon, even the tilt at which he was holding his camera. He was a master of the art of photography. Ansel Adams eye for detail extended into the depths of his photographs, pulling shadows and light together to create movement within his compositions that invoked the awe of the wilderness as he saw it, hoping to capture that image that others would see it as he did. In that, Ansel Adams was a visionary photographer who was ever so successful in invoking the awe of images he saw into the view of others.

Footnotes:

- [1] (Turnage)

- [2] (Turnage)

- [3] (Turnage)

- [4] (Monolith, The Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, California, 1927)

- [5] (Adams, The Negative)

- [6] (Turnage)

- [7] (Monolith, The Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, California, 1927)

- [8] (Monolith, The Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, California, 1927)

- [9] (In Joshua Tree National Monument, California, from Portfolio Two: The National Parks and Monuments)

- [10] (Trailer Camp Children, Richmond, California, 1944 )

- [11] (Adams, Trailer Camp Children, Richmond, California)

- [12] (Adams, Pioneer Mill, Cimarron, New Mexico)

- [13] (Turnage)

- [14] (Turnage)

References

- Adams, Ansel. “Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park.” n.d. Center for Creative Photography. <http://ccp-emuseum.catnet.arizona.edu/view/objects/asitem/search@/2/title-asc?t:state:flow=76f0e97d-89d2-43d2-b256-619f93be6a5a>.

- —. “Pioneer Mill, Cimarron, New Mexico.” n.d. Center For Creative Photography. <http://ccp-emuseum.catnet.arizona.edu/view/objects/asitem/People@25/2362/title-asc?t:state:flow=e5c55b23-b03e-4762-a800-bce54bf61693>.

- —. The Negative. Ansel Adams, 1995.

- —. “Trailer Camp Children, Richmond, California.” n.d. Center For Creative Photography. <http://ccp-emuseum.catnet.arizona.edu/view/objects/asitem/People@25/2486/title-asc?t:state:flow=c25971dd-5aae-4757-94d4-260a07914bf1>.

- “In Joshua Tree National Monument, California, from Portfolio Two: The National Parks and Monuments.” n.d. SFMOMA.org. <https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/51.3209.9#view-artwork>.

- Monolith, The Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, California, 1927. n.d. <https://www.hcc.commnet.edu/artmuseum/anseladams/details/monolith.html>.

- “Trailer Camp Children, Richmond, California, 1944 .” n.d. Housatonic Museum of Art. <https://www.hcc.commnet.edu/artmuseum/anseladams/details/trailerpark.html>.

- Turnage, William. Ansel Adams Biography. n.d. <http://www.anseladams.com/ansel-adams-information/ansel-adams-biography/>.