What Does Literature Do

July 5, 2021

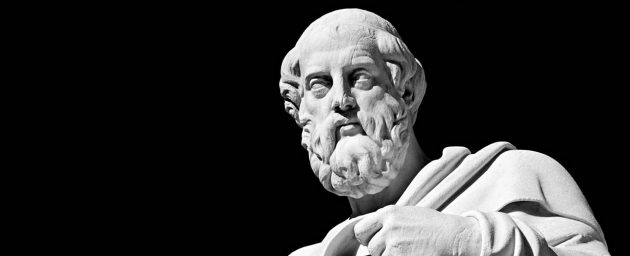

When prompted, in my graduate studies class, Theory and Criticism of Literature, to write about why I turn to literature, I cited literature as a source to understand the human struggle. This question, “what does literature do” was posed after reading an excerpt of Plato‘s Republic. My response follows…

I believe that literature is capable of expanding our minds as it reaches into the depths of the soul of the reader and invites them in to view a glimpse of the human soul from the eyes of the writer and the characters who they write about. Furthermore, I contend that literature can be a great source of comfort and joy to readers and it can also shake a reader to their core causing the reader to feel discomfort, confusion and sadness. To further clarify my own beliefs and broaden my understanding of what literature does, I turned to Plato to examine his beliefs on the topic.

Plato is not terribly concerned with the human struggle. Indeed, the human struggle in literature is only a representation of that struggle in Plato’s opinion. He says in the Republic, Book X that “a representer knows nothing of value about the things he represents” (Plato p. 71). In this Plato asserts that a writer can not know anything about what they are writing about, because writing is a form of representation and “representation and truth are a considerable distance apart” (Plato p. 67).

I would tend to disagree with Plato on this, as I believe that writers are capable of translating their own experiences into literature whether it be poetry, fiction or nonfiction. In fact, in today’s world, which is so vastly different from Plato’s time, the memoir, which falls into the creative nonfiction genre, is a very popular form of literature. Yet, in Plato’s view, “a good poet must understand the issues he writes about, if his writing is to be successful, and that if he didn’t understand them, he wouldn’t be able to write about them” (Plato p. 67).

Plato would like us to believe that poets who write representative poems are creating “products” which are “two steps away from reality and that it certainly doesn’t take knowledge of the truth to create them (since what they’re creating are appearances, not reality)” (Plato p. 67 – 68). But what of the poet who is in love and writes love poetry? Is it not feasible that the poet experiences and understands the meaning of and the reality of love? Love is one of the great inspirational forces for many poets and writers. Their human experience with another person is certainly reality, is it not? If you were to tell a poet, who wrote volumes of acclaimed love poetry, that their poetry was not reality, certainly the poet would balk at that criticism.

And what of the poet who writes about grief, after their beloved has left them, or worse, has passed away. How can one say that the poet is writing representative work and not reality? Reality is very subjective when it comes to human emotions. We each experience and feel emotions differently. Are our emotions and feelings reality or a representation? In the mind of the love struck or grief-stricken poet, what they are writing about is very real. It is their reality, and they wish to share their reality with others, and so they write about it. In this act of writing about their reality, the poet is able to give readers a glimpse of their heart and soul, and they great joy or pain that they are feeling.

How can this be a representation when certain types of emotions, like love and grief share collective and common feelings amongst themselves? Is the poet not sharing in their work their expertise on the very topic that she writes about? I fail to agree with Plato that poetry is merely a representation and not reality for as a poet, I have written on my own experiences with both love and grief. The poems I have written were real to me and to others who read them—my readers experienced a collective understanding of love and grief through my work.

In my view, Plato has some rather dismissive thoughts on bad times and grief, in which he says that “part of our minds which urges us to remember the bad times and to express our grief,” is in fact simply “greedy for tears” (Plato p. 74). These people, Plato infers about are indulging in self-pity and they seem to be incapable of facing “hard work” and “hardship” (Plato p. 74). Have a heart Plato—the reality of life is that people experience great joy, great struggles, and hardship, and it is the very nature of humanity, that we express our experiences with each other, through language and literature.

To dismiss the opportunity for readers to share in the writer’s experiences and reality as a mere representation of the writer’s former “reality” is to dismiss that the writer had any experiences at all, is it not? Plato also alludes that “the petulant art of us is rich in representable possibilities,” while intellectual part of our characters is pretty well constant and unchanging” (Plato p. 74). Here we see that intellect is gone from the representational mind of the poet, who is purely interested in retaining their “popular appeal” (Plato p. 74). Furthermore, a representational poet is capable of creating and thus invoking in readers, something akin to a “bad system of government,” by “gratifying their irrational side” (Plato p. 74). Poets do bad things in Plato’s argument and “representational poetry” is capable of “deforming even good people” (Plato p. 74). How does this happen one would ask?

A poet has the ability to satisfy and gratify aspects of the human spirit “which we forcibly restrain when tragedy strikes our own lives—an aspect which hungers after tears and the satisfaction of having cried until one can cry no more” (Plato p. 75). This is messy stuff that poets bring up in readers. It is better to be more reserved and restrained as Plato notes, “when hardship occurs in our own lives” (Plato p. 75). That might have been the case in Plato’s time, but in today’s world people are accustomed to sharing collective experiences of love, joy, pain, and suffering, and in this vast collection of these experiences, known as literature, that poets and writers all share with each other, we are all capable of acknowledging the both the frailty and the resilience of the human spirit.

This is what literature does. It gives the reader the ability to grow and learn, to connect with like minds, to share words, thoughts and feelings, and it provides us with the opportunity to go places we’ve never been before, for literature can transport us and it can even save us when we most need salvation.

References

Plato. “Republic.” Leitch, Vincent B, et al. The Norton Anthology of Theory & Criticism. New York, London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010, 2001. p. 64 – 77. Print.